Barrister Without Borders

Amal Clooney LLM ’01 has built an unparalleled human rights law practice that reaches around the globe. NYU Law is where she found her passion for international law.

Philippa Webb and fellow barrister Amal Clooney LLM ’01 were catching up by phone, Webb remembers, when the sounds of exploding bombs on Clooney’s end interrupted their chat. “She says, ‘Oh, I’m just going to pop under the desk,’” recalls Webb. “I was panicking at the other end…. She was very calm about it, because I think she adapted to what was a high-risk environment.”

At the time, Clooney was an investigator for the United Nations in Lebanon, living in a mountaintop compound behind four security checkpoints. Born Amal Alamuddin in Beirut in 1978, Clooney fled the Lebanese civil war with her family when she was a toddler, resettling near London—so her Lebanon assignment was uniquely compelling, says Webb, now a professor of public international law at King’s College London. Clooney later spent several years working for the first UN terrorism tribunal in The Hague, created to prosecute Hezbollah members accused of perpetrating a 2005 attack that killed more than 20 people, including former Lebanese prime minister Rafic Hariri.

Today, Clooney is a barrister at London’s Doughty Street Chambers focusing on international human rights law, public international law, and international criminal law, as well as co-founder of a foundation that “wage[s] justice to protect the human rights of the most vulnerable.” Her résumé could double as a checklist of some of the world’s highest-profile legal battles over the past two decades—particularly those involving media figures and victims of mass atrocities. Clooney’s more famous clients have included Yulia Tymoshenko, former prime minister of Ukraine, and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Clooney has also represented reporters such as Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa of the Philippines, Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo of Myanmar, and Egyptian-Canadian journalist Mohamed Fahmy, all of whom faced spurious charges and prison time.

While Clooney’s first exposure to international law occurred at the University of Oxford—where she studied jurisprudence as an undergraduate—NYU Law was where Clooney fell in love with the field. “NYU was the perfect complement to my Oxford law degree,” says Clooney. “While my studies at Oxford were quite theoretical—I even studied Roman law—NYU was all about real-life application of the law, which I found thrilling.”

Clooney has made the violence committed by ISIS against the Yazidis, a Kurdish religious minority living in Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran, a central focus of her human rights litigation efforts. In 2021 in Frankfurt, Germany, Clooney represented a Yazidi victim in a trial ending in the first-ever conviction of an ISIS member for genocide; she has represented victims in seven other German cases, as well as cases against ISIS members in the Netherlands and the United States. Her most prominent Yazidi client is Nadia Murad, who was held by ISIS and subjected to sexual violence after the group killed most of her family and village. Escaping captivity, Murad became an activist and UN goodwill ambassador and won the Nobel Peace Prize. She is the lead plaintiff among more than 400 other Yazidis in Clooney’s biggest current case: a civil suit filed last December in the US District Court for the Eastern District of New York against French cement manufacturer Lafarge, which operated a facility in an ISIS-occupied area of Syria and paid ISIS and an associated group nearly $6 million while ISIS was committing violent crimes against Americans and Yazidis.

“The lesson is it costs money to commit crimes like this and crimes at this scale, and we have to continue to pursue justice in every forum,” Clooney said in a CNN appearance at the time of the Lafarge filing. (According to Webb, a number of Yazidi women have named their daughters Amal in Clooney’s honor.)

“She’s groundbreaking when it comes to law,” says Helena Kennedy, a founding member of Doughty Street Chambers. She notes that Clooney “drew the map” for Germany’s use of genocide law to prosecute ISIS terrorists, and she emphasizes Clooney’s knack for lateral thinking in devising litigation, calling her “smart as hell.”

“She will know every fact,” says Webb. “She will bottom out every legal issue…. I don’t know anyone [else] who combines that strategic, high-level thinking with the warmth and genuineness of client communications and the nitty-gritty of the legal detail.”

Webb and Clooney collaborated on The Right to a Fair Trial in International Law (Oxford University Press, 2021), which tackles a fundamental question: What is the international standard for a fair trial? The two aimed to articulate a universal standard, grounded in 13 different component rights that could be applied in countries and international forums around the world. According to Kennedy, the product of their work has swiftly become “the go-to book” for international law practitioners and judges. Webb notes that the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom has incorporated the book’s concept of 13 disaggregated rights into its own reasoning regarding fair trials.

Accepting NYU Law’s Alumni Achievement Award at her 20-year reunion in 2021, Clooney recalled her LLM days: “If I’m grateful for one thing above all about this time, it’s that my NYU Law professors took a chance on me.” Clooney applied and was selected for an externship in the chambers of Sonia Sotomayor, then a judge on the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, even though such positions typically went to JD students. Clooney also was able to take a constitutional litigation course co-taught by adjunct professors John Koeltl and Leonard Sand—both US district court judges—despite not having taken the prerequisite constitutional law class.

“They gave me a chance, I worked twice as hard, and my dream of arguing in a courtroom was cemented,” says Clooney.

Clooney was an efficient student who could put in some quick study time right before her exams and still make top scores, recalls Airi Hammalov LLM ’01, who was one of Clooney’s roommates in D’Agostino Hall. Another former roommate, Irina Taka ’03, says she remembers first and foremost Clooney’s “instinctive, natural kindness no matter what, from the doorman to the dean, irrelevant of the person.” Taka says that, for Clooney, “what she wanted to learn came first, and then she always found a way to do it…. She managed to be genuinely passionate, but without being annoying or preachy.”

David Golove, Hiller Family Foundation Professor of Law, says that Clooney excelled in his seminar on global justice. “She’s matured into a really sophisticated, eloquent, elegant advocate and lawyer,” says Golove. “And none of that surprises me, because it was there from the beginning.”

After NYU Law, Clooney landed a litigation associate position at Sullivan & Cromwell in New York, even though foreign LLM graduates typically pursue corporate law. Samuel Seymour, then a partner and head of the white-collar criminal defense practice group, recalls working with Clooney to represent David Duncan, a former partner at accounting firm Arthur Andersen, in Enron-related litigation. After pleading guilty to obstruction of justice, Duncan was the government’s star witness in the ensuing trial. Clooney was instrumental in helping to explore the complexities of the case, Seymour says. Just as important, he adds, “[Amal] was really great with David, and she was able to help explain these principles…[but also] be a human and help him through a very difficult time.”

Clooney’s talent for creative legal thinking played a crucial role. At her suggestion, the firm sought a continuance of Duncan’s sentencing while Arthur Andersen appealed its own obstruction of justice conviction. When the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the accounting firm, Duncan’s conviction was also overturned, even though he had already pleaded guilty. Seymour says he has seen no other such examples in his four decades of practice.

It was international law, however, that most intrigued Clooney. During her LLM year and early practice in New York, Clooney recalls, “I started to see how all my interests—in courtroom advocacy, in representing victims, in using the law to address conflict—could come together.” While working at Sullivan & Cromwell, she got back in touch with her former professor Golove and successfully applied for a one-year clerkship at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague; in 2000, NYU Law had become the first American law school to launch such a clerkship program. Clooney’s time in The Hague would prove determinative.

She arrived during former Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milošević’s lengthy war crimes trial. Clooney, who took a role with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia after her ICJ clerkship, was involved with drafting the judgment in the case before it became moot at his death in 2006. She planned to return to New York to practice—until she heard about the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. Clooney then spent years pursuing justice in her native country—bombs or not—before joining Doughty Street Chambers in 2010.

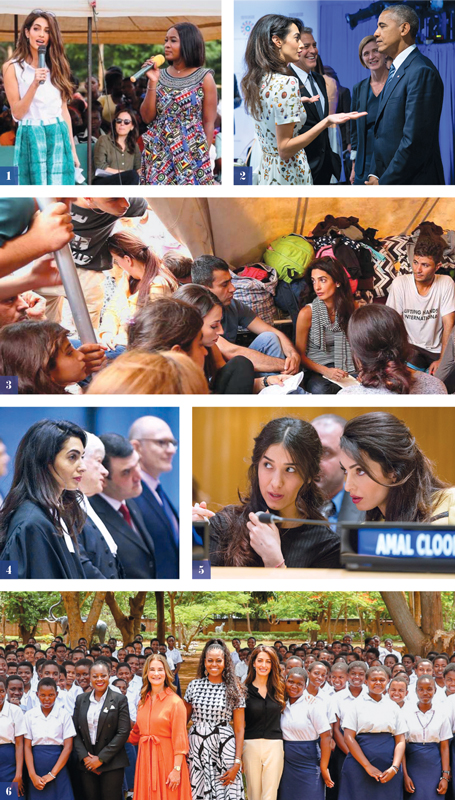

Clooney’s most public-facing endeavor may be the Clooney Foundation for Justice (CFJ), which she co-founded in 2016 with her husband, actor and filmmaker George Clooney. Working in more than 40 countries, CFJ focuses on three initiatives: TrialWatch, which monitors criminal trials against journalists and other vulnerable groups and has prevailed in every case taken to an international body; the Docket, whose participants investigate mass atrocities to trigger prosecutions and represent victims; and Waging Justice for Women, which litigates against discriminatory laws and gender-based abuse. The last initiative includes legal aid clinics across Africa and a collaboration with Michelle Obama and Melinda French Gates supporting the education and empowerment of adolescent girls. Professor of Clinical Law Margaret Satterthwaite ’99, UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, says that CFJ is doing “crucial work…to make sure brave justice advocates can continue to advance human rights despite threats, criminalization, and harassment.”

TrialWatch, Webb says, shows how CFJ bolsters Clooney’s other work. Their fair trial book informed UN training of TrialWatch observers. A co-developed Microsoft app helps collect data, which legal experts use to grade trials, building a global justice index to measure progress and to advocate for change. “That’s the scaling up and the innovation that the foundation brings,” says Webb. “It’s not just one thing. It’s seeing through a process of change [that’s] really grounded—because it’s Amal—in completely solid legal research and analysis.”

While her marriage has brought unsought celebrity, Clooney continues her human rights work as before. In 2022, named one of Time’s Women of the Year, she told the magazine, “In terms of an increased public profile, I think all I can do is try to turn the spotlight to what is important.”

Clooney’s current work, in addition to the Yazidi litigation, includes representing the Maldives as an intervenor in an ICJ case concerning the Myanmar military’s alleged genocide against the Rohingya people. She does not shy away from difficult legal questions: earlier this year, she served—along with Theodor Meron, Charles L. Denison Professor of Law Emeritus—on a panel of legal experts that reviewed the International Criminal Court prosecutor’s investigation into war crimes in the Israel-Gaza conflict, resulting in an application for arrest warrants for Hamas and Israeli leaders. Recently Clooney co-edited Freedom of Speech in International Law (Oxford University Press, 2024) with former UK Supreme Court president David Neuberger, and has been co-teaching a human rights course at Columbia Law School. She also mothers her young twins.

Clooney “has made a huge contribution in a range of important human rights cases over a period of many years,” says Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law. “She is a leading advocate in all senses of the word.” Awards from the United Nations Correspondents Association, the American Society of International Law, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, and the Simon Wiesenthal Center have recognized her legal advocacy.

“Despite all the attention…she hasn’t lost touch with who she is at her core, and I think credit for that obviously goes to her [and her family],” says Webb, adding, “She’s passed on [to her children] that strong and grounded sense of self that celebrates others, that hopes for the future, that wants to make a difference in the world. She was always like that. Now she just has a bigger platform from which to execute those ambitions.”

Atticus Gannaway is senior writer at NYU Law.

Photo credits: Getty/Marla Aufmuth (first image). Other photos courtesy of Amal Clooney. 2. Pete Souza; 6. Neil Rasmus

Posted September 10, 2024