The Law of Memes: Amy Adler and Jeanne Fromer argue that memes, which raise questions about conventional notions of copyright law, have considerable legal and cultural significance

Internet memes—digital images, created by combining visual media with captions, that are disseminated online—can be difficult for legal scholars to take seriously. That becomes slightly easier in a world that includes moneymaking meme superstars such as the late Grumpy Cat, who generated earnings for her owner through live appearances and licensing agreements featuring the dour feline’s likeness.

In their NYU Law Review article “Memes on Memes and the New Creativity," Emily Kempin Professor of Law Amy Adler and Professor Jeanne Fromer argue that memes are important for reasons beyond online ubiquity and potential monetization: they upend traditional understandings of copyright law. “Academics tend to dismiss meme culture and to think of it as some sort of abject, Gen-Z joke that everyone hopes will pass,” said Adler during an NYU Law Forum, sponsored by Latham & Watkins, in November, in which she and Fromer described their findings. “…It’s tempting to see memes as nothing more than pathetic shards of pop culture, but we take memes seriously because they pose important challenges for traditional ideas about creativity and law.”

The article begins by exploring “copyright law’s deep-rooted assumptions of creativity, commercialization, and distribution,” which have not shifted dramatically since the invention of the printing press gave rise to that area of law. In particular, copyright law takes as a given that copying others’ works is harmful, even though fair-use exemptions exist. The rationale is that copying reduces the incentive for creators to create and makes their works harder to monetize. Copyright law makes other assumptions, too: that authors of a given work are central to its production and easily identified, and that they typically would wish to license their work to a select few rather than many.

In a world characterized by ever-shorter attention spans and an increasingly visual culture, memes have become both wildly popular and powerful, including in the political realm, the co-authors say. But current copyright law, they add, seems ill equipped to deal with memes, particularly because the idea of copying an original work—usually an image—is intrinsic to memes.

As the article points out, going viral through mass copying is what actually creates worth for a meme. “This is true not only of meme creators, but many creators in the digital environment, who understand that if images or clips of their works become memes, this will ultimately add value to the original work or to whatever else the creator may be marketing,” Adler and Fromer write. “Nothing in copyright theory can describe this or even fathom it.” Traditional artists increasingly embrace memes that incorporate their works. For instance, the rapper Drake designed the music video for “Hotline Bling” to be easily memed, contributing to the song’s success.

Memes, Adler and Fromer explain, highlight other copyright peculiarities, such as the blurred line between commercial and noncommercial activity. Memes also muddy the distinction between expression, which is copyrightable, and an idea, which is not. That difference, they suggest, becomes vaguer still in the world of memes in which canonical expression is transformed into idea. Further, memes, most of which have a brief shelf life, raise questions about the long duration of copyright—typically the author’s life plus 70 years—that experts have already questioned in other contexts.

The co-authors invoke the trope of the reclining Venus, painted in new variations across the span of centuries, as an example of a proto-meme that parallels the digital meme phenomenon. They also suggest that the recent, highly speculative market for non-fungible tokens (NFTs) stems from an urge to privatize widely available meme images: “an attempt to cling to the concepts of uniqueness, originality, and authenticity in a world where those concepts no longer make sense.”

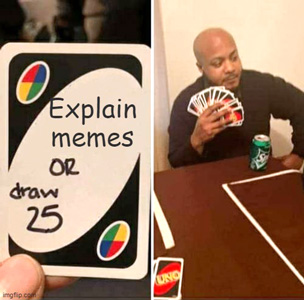

Before collaborating on the new article, Adler and Fromer had discussed memes for a long while, both together and in their individual scholarship. As Adler explained during the Forum, the two share an interest in pop culture, “low” culture, and digital culture. That mutual interest led to a novel choice, said Fromer: illustrating their forthcoming article with memes “to reflect back on meme culture and how it’s affecting or could affect copyright law and creativity, among other things.” For example, the section about the “elastic and imprecise” meaning of “meme” includes a meme of a man drawing 25 Uno cards rather than explaining memes. Their discussion of the ephemeral nature of memes is illustrated with the meme of a man ogling a passing woman, “Just-Posted Meme,” while his romantic partner, “Meme Posted Yesterday,” glares at him.

If we want to preserve a thriving meme culture, Adler and Fromer write, some adjustments are necessary. They analyze the pros and cons of different options, which include establishing norms tolerant of copying and favoring copyright nonenforcement for memes; giving attribution to meme creators, transformers, and distributors; creating alternate, brief copyright durations for memes; narrowing the scope of copyright for memes in relation to other works; and addressing the First Amendment issue of selective copyright enforcement, sometimes employed by meme creators against only a few parties whose use of their meme the creators find objectionable.

Memes, Adler and Fromer assert, typify “a new mode of creativity that is emerging in our contemporary digital era.” Although traditional creativity will retain an important place, they add, the copyright issues raised by the proliferation of memes will likely become only more generally applicable: “While the traditional path might be cultivated best with copyright law, the new path should not be, at least with copyright law in its current form.”

Watch the video of the NYU Law Forum with Amy Adler and Jeanne Fromer:

Posted January 19, 2022

Updated August 9, 2022

Top photo credit: Adobe Stock/Photocreo Bednarek

Meme credits: Know Your Meme